|

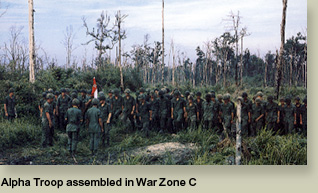

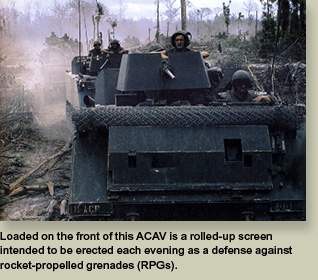

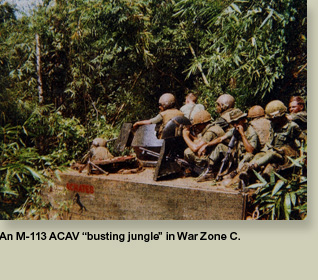

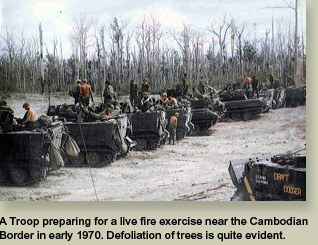

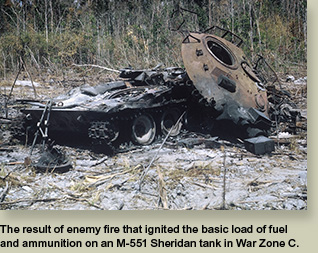

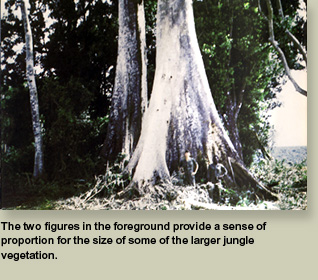

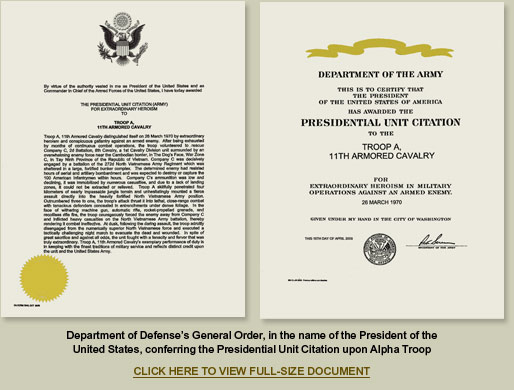

Ordinary Men, Extraordinary Soldiers “In the end, it was just the men,” wrote Capt. John Poindexter (ret.) in his book, The Anonymous Battle. “Always the men.” Some 300 of them on the ground in the U.S. Army’s Alpha Troop, 1st Squadron, 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment’s epic battle of March 26, 1970. At least 75 men from the three military units engaged in the battle and its grim prelude the evening before would be wounded or killed. Even before a horrifying mortar accident on March 25 and the daring March 26 rescue of an infantry company hopelessly trapped by the North Vietnamese, Alpha Troop was battered and weary. But by midnight on March 26, Alpha Troop — also known as A Troop — had accomplished what had seemed almost impossible. It had rescued Charlie Company, an airmobile unit of the 8th Cavalry, 1st Cavalry Division, whose men were facing imminent death or capture as their losses mounted and supplies ran low. “I will always remember what Alpha Troop, 1/11 ACR did for us,” retired Private First Class Paul Evans said in The Anonymous Battle. “I feel that if Alpha Troop had not come to rescue us, I would have been killed or missing in action. I can only speak for myself, but I am sure my fellow troopers feel the way I do.” The night before Sometime after 11 p.m., after officers had made their last check of the troop’s night defensive perimeter in a small jungle clearing deep within War Zone C, the troopers finally settled in for some badly needed sleep. The troop’s guards were maintaining their nightly vigil, the mortar teams were firing scheduled defensive volleys, and all else was calm on this typically sweltering night on the Cambodian border. But the quiet evening was shattered as one of A Troop’s armored mortar vehicles exploded in a fireball, tearing apart the men inside and creating such intense heat that sections of the vehicle melted. As the heat from the initial blast caused additional mortar shells inside and around the vehicle to explode, the entire encampment was catapulted immediately into action. Some soldiers, one of whom died himself, tried vainly to rescue the men inside the engulfed vehicle. Others leapt into nearby ammunition-laden armored vehicles to drive them away from the oven-like heat of the inferno. All worried that the accident had so illuminated the troop’s position that Vietnamese soldiers would soon take advantage of the situation and launch an artillery assault on Alpha Troop. The rescue March 26 also brought the alarming and unmistakable sound, from about four kilometers away, of American troops being gradually overwhelmed by an elite North Vietnamese Army battalion. The distant sounds of rifles, machine guns and rocket propelled grenades were punctuated by radio contact between the pinned down Charlie Company and its infantry battalion and division commanders circling overhead. Within hours, A Troop’s officers and crewmen knew Charlie Company was in serious trouble, running low on ammunition and incurring serious casualties inflicted by an entrenched and determined enemy force. The troop’s experienced officers knew that their position was close enough— maybe – for Alpha Troop to do something about it, though heavy losses were guaranteed if it tried. “The perspiration ran more freely than usual,” Poindexter later wrote, “as each of us pondered the agonizing choice between lifelong guilt and the certainty of immediate suffering.” Ultimately, there was really only one choice. Alpha Troop would volunteer to saddle up, head for Charlie Company’s position, and attempt a violent, almost reckless rescue of their Army brothers. A Troop, no matter how weary, simply could not listen impotently as its comrades were killed or marched by night to enemy base camps in nearby Cambodia. Traveling with the troop, mounted atop its armored vehicles and soon to play a bloody role in the inevitable battle, was Alpha Company, 2/8 Cavalry, an airmobile infantry unit from Charlie Company’s battalion. The jungle-busting journey to the surrounded Charlie Company required hours of skillful maneuvering around old B-52 bomb craters, constant clearing of fallen tree limbs from gasping engine air intakes, and each man’s struggle to control his growing anxiety about the way ahead. Progressing no faster than 100 meters every five minutes and with the navigational assistance of Charlie Company’s battalion commander surveying the trackless jungle from a helicopter above, A Troop at last reached Charlie Company. The men of Alpha Troop and Alpha Company were relieved — and astonished — to have avoided an ambush as they approached the battle site. Apparently, the C Company infantrymen had unwittingly penetrated a massive underground North Vietnamese bunker complex of the seasoned 272nd North Vietnamese Army Regiment that was concealed beneath the forest canopy. Through the unimaginably dense jungle vegetation, however, no one could discern just how big or well fortified the hidden complex was. Shortly after 5 p.m., A Troop’s men and armor were in position, having formed an assault line and prepared their weapons for a desperate drive directly into the invisible entrenchments of the enemy. The Alpha Company grunts had dismounted from the vehicles and scattered into the brush just behind the vehicles, ready to fire their rifles and heave grenades while advancing. Just to their south, Charlie Company’s approximately 30 wounded men knew A Troop was all that stood between them and a powerful enemy force anxious to kill or capture them as it had killed three C Company men already. There was a disconcerting calm for a moment from both sides of the battlefield. And then the fateful command: “Commence fire!” The heavily armed A Troop, moving inexorably forward, unleashed assault after furious assault on the heavily fortified NVA bunker complex. The Americans’ .50 caliber machine guns heated up to the point that some nearly welded themselves together. Their massive Sheridan tank guns disintegrated bunkers and reduced small trees to splinters. The North Vietnamese valiantly and all too effectively fired back with rocket propelled grenades, machine guns and rifles from within their buried fortifications. The battlefield quickly became littered with shell casings, empty ammunition cans, untold tons of shredded vegetation, and disabled tanks and armored cavalry assault vehicles. As the troop pressed forward, each armored vehicle fought it out with individual NVA bunkers or small complexes of them. The machine guns of the cavalry fired ahead and down toward the enemy fortifications, often invisible in the underbrush, while the determined NVA regulars launched RPGs and fired automatic weapons from only feet away. Sometimes the light aluminum hulls of the cavalry vehicles held and the troopers ruthlessly crushed the entrenchments. Other times, the Americans were swept by fire from the tops of their ACAVs or the armored vehicles themselves were crippled until the crews could spur them back to the attack with hasty repairs. Meanwhile, the battered but reinvigorated Charlie Company engaged mobile NVA troops probing the vulnerable rear of Alpha Troop and Alpha Company’s line of advance. A Troop was supported throughout the attack by the 8th Cavalry’s Alpha Company, commanded by Ray Armer, whose troops on the ground were just as relentless as Alpha Troop’s crewmen. Together, they were known as “Team Alpha” and they formed as fierce and seamless a fighting force as the North Vietnamese likely had encountered. Nonetheless, it was becoming ominously apparent that the enemy bunker complex was far larger than any that Alpha Troop previously had experienced and that the troop’s onslaught was being contested courageously by the NVA. It was also evident that the determined enemy greatly outnumbered the Americans still able to fight and that the risks to the casualties, to whom only field first aid could be given, were escalating drastically. Shadows grew long as the afternoon light faded. Alpha Troop now faced a painful and tactically complex reality: With daylight slipping away, there wasn’t enough time left to force the NVA from its relatively secure bunkers and into open retreat before dark. Nor was the remaining daylight sufficient to allow the troop to clear a landing zone for the evacuation of the dead and wounded and to provide even a small jungle clearing for a new night defensive position. And, unless the troop returned soon to the old NDP of the night before to retrieve the rear element left behind, those exposed troopers would be at the mercy of the NVA. Finally, there was a new dilemma to confront as mobile enemy troops established a blocking line to the south. Team Alpha and Charlie Company were now encircled just as Charlie Company had been. And all were running out of time. The firefight built toward a crescendo as dusk approached with neither side showing any sign of yielding. At the peak of the assault, First Sergeant Robert Foreman, one of the most respected non-commissioned officers in the troop, took a direct hit from a rocket propelled grenade on his tank’s gun shield and was killed instantly. The same blast knocked Poindexter and his fighting crew temporarily unconscious and wounded each man with flying shrapnel. All friendly fire ceased in that sector of the line, a disastrous opening that invited a merciless NVA reaction. Ray Armer quickly leapt onto the unprotected rear deck of Foreman’s Sheridan tank and fired its .50 caliber machine gun until Poindexter’s crew partially recovered from the RPG blast and returned to their weapons. Critically, Alpha Company’s infantrymen moved up to the line to suppress the rising influx of RPGs and automatic weapons fire. Stability soon was restored to the American line of attack but the decisive forward impetus slipped away. By 7 p.m., as darkness began to envelop the battle, A Troop had no choice but to attempt to return to the previous night’s defensive position in the clearing where the tragic mortar accident had occurred. There simply wasn’t enough daylight, ammunition or manpower left to dislodge the enemy from entrenchments whose size remained a mystery. And the potential for more deaths among the growing number of wounded, denied access to critical hospital care, was not abating. After a brief respite, sporadic automatic weapons fire erupted as the Americans began to disengage and to force their way through the encircling enemy on their southern perimeter. The slow trip back to the old night defensive position was agonizing both for the wounded and the crews who expected an NVA ambush at any moment. The survivors of the shattered mortar section faultlessly fired aerial illumination rounds without which the armored vehicles, laden with their broken human cargoes, could never have navigated the black jungle. At last, back at the previous night’s clearing, the helicopter airlift of the wounded and dead continued for hours. The smells of blood and dust and diesel fumes wafted through the night air along with the sounds of the wounded and the roaring of the medevac choppers. The chaos of the firefight and the ensuing evacuation of the wounded and dead made it difficult to calculate an exact tally. However, it is estimated with considerable confidence that among the three American units on the ground, seven died and at least 68 were wounded. This count did not include the wounded who refused evacuation from the field, those flown out on non-medevac missions and the unknown number of wounded who ultimately succumbed to their injuries. First Cavalry division headquarters set North Vietnamese losses at 88. No one ever named the battle fought to rescue Charlie Company and many might conclude that the casualty totals made the fearsome confrontation a draw. But in the end there was one irrefutable certainty: Charlie Company was home. The Presidential Unit Citation After a comprehensive, almost five-year review of the supporting documentation, the Department of Defense approved the award of the PUC in November 2008, and the general order promulgating the decoration was published in April 2009. A unit receiving the Presidential Unit Citation “must display such gallantry, determination and esprit de corps in accomplishing its mission under extremely difficult and hazardous conditions as to set it apart and above other units participating in the same campaign. The degree of heroism required is the same as that which would warrant the award of a Distinguished Service Cross to an individual.” According to public records, the PUC has been authorized 127 times, including Alpha Troop’s award, going back to World War II. (This tally treats the Third Infantry Division’s PUC, granted for its service in Iraq, as one award.) George Hobson, who commanded Charlie Company and whose men A Troop rescued in March 1970, calls the PUC long overdue recognition for Alpha Troop’s selflessness, dedication to duty and commitment to fellow soldiers. Like Poindexter, Hobson hopes all combat veterans of Vietnam will recognize that this award helps to illustrate that after so many years, our country is at last celebrating and honoring the men — the “grunts” and “troopers” — whose daily acts of heroism and valor became ordinary in the brutal firefight that was Vietnam. Individual decorations |